REVIEWS

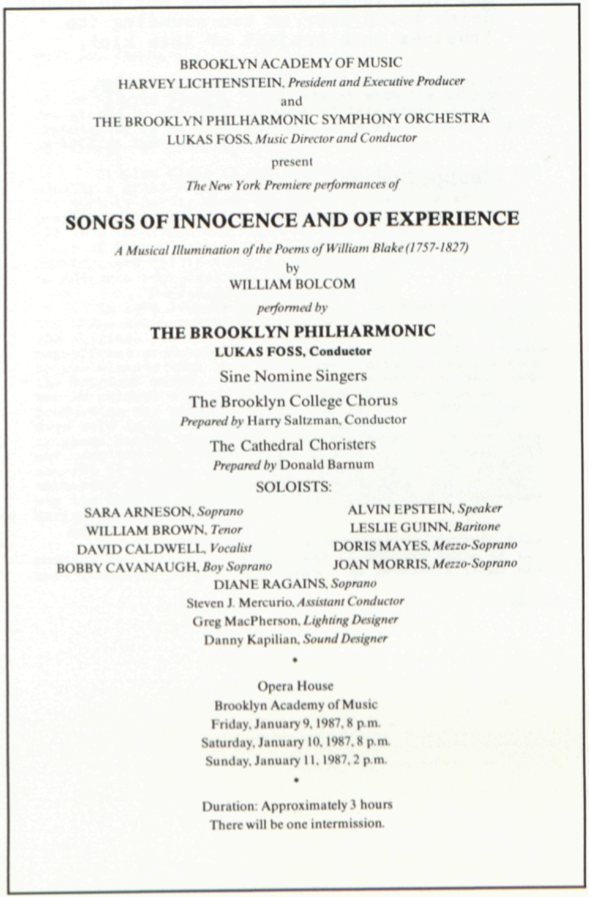

William Bolcom, composer. Songs of Innocence and of Experience, A Musical Illumination of the Poems of William Blake. New York premiere at the Next Wave Festival. Brooklyn Academy of Music, 9-11 January 1987. Brooklyn Philharmonic, Lukas Foss, conductor.

After hearing the piper piping again in William Bolcom’s symphonic rendering of Blake’s Songs, one rereads them as what they always were: a cantata with human voices joining a chorus of birds and beasts and all nature providing orchestration.

On the “Ecchoing Green” the skylark, thrush, and “merry bells” ring in the morning; a “Cradle Song” lulls an “infant joy,” and beetles hum through the “silent delight” of night. The lamb trumpets in call and response to the ewe’s “tender reply,” inspiring the shepherd’s tongue to his own psalm of praise. Correspondingly, “when voices of children are heard on the green,” the green woods, the air, the dimpling stream, the meadows, the grasshopper, and the painted birds all add their various strains to the cosmic “Laughing Song;” a fly dances to an intoxicated rhythm, and the nightingale, the lark, and the crowing cock punctuate the pervasive “Infant noise.”

begin page 153 | ↑ back to topIn counterpoint to this joyful melody, a darker theme weaves its “notes of woe.” The “sobbing, sobbing” of the urban robin and sorrowful wren mingle with the chimney sweeper’s “weep, weep,” the “infant groan” and orphans’ “trembling cry.” The harlot’s bawdy taunt and the dirge of a “Soldiers sigh” sound in the cacophony of London streets where, amid a vast moaning chorus around the altar of industrial slavery, weeping parents deliver piteously shrieking children to the roar of furnaces and din of clanging hammer and anvil, the drumming heartbeat of this tigerish city.

Beyond both the spontaneous cries of life, of pleasure and pain, and the mechanical rhythms of grinding mills, the Bard creates songs that reverberate with the harmonious thunder of the multitudes. The “School-Boy,” torn from the sweet accompaniment of lark and huntsman’s horn, has been forced to “Sit in a cage and sing,” and priests, muttering their pious rounds, have manacled every throat and voice in a stifled squawk. But, the poet troubadour of streets and lanes continues to call forth a vibrant ale-house chorus to raise up his hymn to the “human form divine.”

We know from J. T. Smith that Blake composed tunes for his poems which “he would occasionally sing to his friends” and that “his ear was so good, that his tunes were sometimes most singularly beautiful and were noted down by musical professors.” Allan Cunningham informs us that when Blake created, “As he drew the figure, he meditated the song which was to accompany it, and the music to which the verse was to be sung, was the offspring too of the same moment,” but since he “wanted the art of noting it down, . . . we have lost melodies of real value.”1↤ 1 G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969) 457, 482.

Blake’s great visual art might distract us from all this music in his songs, but it is clear why many modern composers have tried to bring aspects of his rich and varied

begin page 154 | ↑ back to top symphony to our ears. Benjamin Britten, Ralph Vaughn Williams, Virgil Thomson, and Samuel Adler have all set groups of the Songs to music. Ben Weber wrote a Symphony in Four Movements on the Poems of William Blake (1950). Ellen Raskin set some of Innocence to guitar for children, and Allen Ginsberg recorded his harmonium chants. Wilfrid Mellers[e] began but never completed the entire cycle; John Sykes (1909-62) finished thirty seven songs.

At this “Enormous Labor,” no one has been more tenacious than William Bolcom, who spent twenty-five years setting all forty-six poems for his Musical Illumination of the Poems of William Blake, a massive megascore requiring as many as 200 singers and 100 musicians. Running almost three hours, this neo-Mahlerian “Symphony of a Thousand,” twice as long as Beethoven’s ninth symphony, is a monumental montage of lyrics for an epic Blake. After previous renditions in such radically different venues as the Stuttgart Opera, Chicago’s park concerts, and the University of Michigan where Bolcom teaches, the Songs had its successful New York premiere in January 1987 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s avant garde Next Wave Festival with Lucas Foss conducting the Brooklyn Philharmonic. Although no recording is yet planned due to the costs of assembling such forces, some further performances, probably in Europe, are projected for 1988.

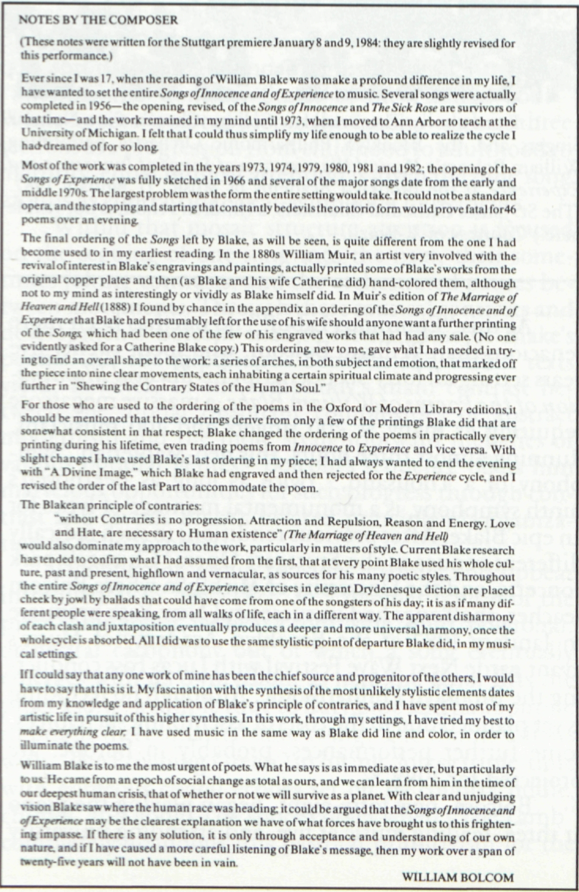

Bolcom, now forty-eight, began playing the piano at three, reading music at five, and attending university classes at eleven. He reports that, upon first encountering Blake at age seventeen in 1956, he “felt an immediate kinship” and set to music then the “Piper’s Song” that opens the piece.2↤ 2 Quotations from Bolcom are drawn from his “Program Notes,” other materials made available to me by the composer and comments reported in such media as the Village Voice, New York Times, and New Yorker. Throughout the 60s and 70s, while working as a teacher, composer, and piano player, he continued orchestrating the poems in what he hoped would be, like Blake’s illustrations, an “illumination.”

The composer cites Blake as precedent for his own attempt to combine the classical and the popular. After getting a graduate degree from Stanford, becoming a Rockefeller and Guggenheim fellow, and studying with the French composer Darius Milhaud, he wrote “serious” modern music in the prevailing dissonant mode—a few symphonies, eight string quartets, piano etudes. Then in 1963 Bolcom dropped out to write an off-Broadway “opera for actors,” Dynamite Tonight, with Arnold Weinstein, discovered a gift for ragtime piano, wrote his Ghostly Rags, collaborated with Eubie Blake and began composing his Unpopular Songs, using classical techniques in pop styles and influencing such rock groups as Pink Floyd. After teaming up professionally and personally with mezzo-soprano, Joan Morris, (they walked down the aisle in 1975 to a ragtime Wedding March played by ninety-six-year-old Eubie), he became best known as her accompanist. They soon gained renown for bringing American popular music to classical labels and concert halls with wit, charm, and artistic seriousness. After earning a Grammy nomination for After the Ball, a collection of pre-1920s tunes (Nonesuch) which topped the classical charts, they followed with anthologies of vaudeville songs, Civil War era ballads, songs by Gershwin, Kern, Rodgers and Hart, and cabaret tunes, many by Bolcom, recorded on two live albums, Black Max and Lime Jello (RCA)—fourteen recordings in all. Bolcom never entirely stopped writing more formal modernist music, however, and the week of the Blake premiere also saw both a concert of popular songs with Morris and a performance of his violin concerto at Carnegie Hall. Soon after, the St. Louis Symphony would perform his Fourth Symphony, developed around an extended setting of Theodore Roethke’s “The Rose.” In preparation for setting poetry to music, Bolcom had studied at the University of Washington with Roethke, whose use of old poetic forms such as the villanelle parallels Bolcom’s own mining of traditions. Here the main musical influence was the composer Charles Ives whose celebration of popular American idioms and emphasis on accessibility would influence such diverse other composers as Kurt Weill, Virgil Thomson, Leonard Bernstein, Lukas Foss, George Rothberg (whose writings Bolcom edited), David Del Tredici and Peter Schickele.

However, the confidence and theory for this eclecticism, according to Bolcom, came from Blake: “Blake begin page 155 | ↑ back to top used his whole culture, past and present, highflown and vernacular as sources for his many poetic styles” with “elegant Drydenesque diction placed cheek by jowl by ballads that could have come from the songsters of his day . . . as if many different people were speaking, from all walks of life.” The Songs, Bolcom’s most ambitious attempt at synthesis, which he alternately calls a symphony-oratorio or cantata and compares to song cycle, opera, glee club concert, and rock album, pushes traditional composers’ incorporation of folk motifs to new limits. Bolcom complains that “some composers have become so concerned with being one-pointed. You can become imprisoned that way. Bach and Mozart constantly brought some of the pop music of their day into their music.” What differentiates Bolcom’s work from more traditional borrowers, like Dvorak, who work classical embellishments on stolen snippets of popular melodies, is that Bolcom eschews such classical reworking and allows each vernacular style its own character. Instead, he explores the contrasts which result from letting rock and folk jostle alongside dissonant twelve-tone chorales. He attributes his “fascination with the synthesis of the most unlikely stylistic elements” to his knowledge and application of Blake’s principle that “Without Contraries is no progression.” In his wide variety of musical settings, he seeks to mirror the scope of Blake’s work itself so “the apparent disharmony of each clash and juxtaposition eventually produces a deeper and more universal harmony, once the whole cycle is absorbed.”

In order to achieve this range, avoid tedium and give maximum color to the lengthy work, he employs a massive panoply of musical forces in a three ring circus

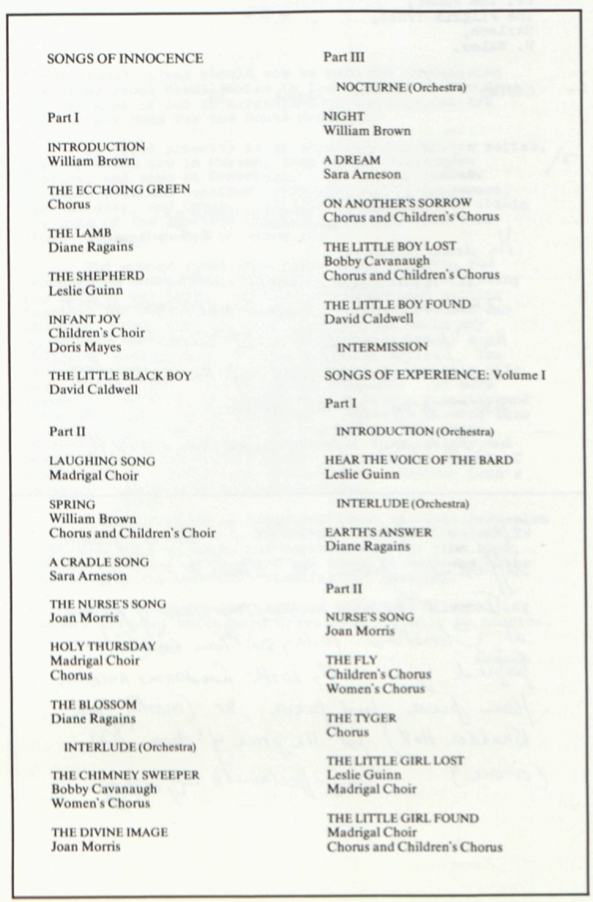

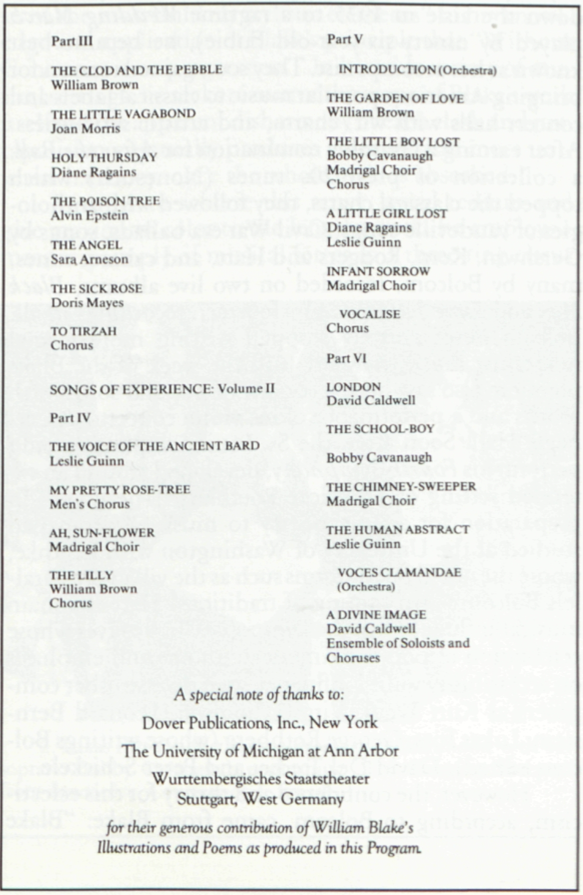

He has found his order for the texts in one of the last of Blake’s reorderings (indicated in a late letter, perhaps to Butts, E 772), a version existing in only one copy. Bolcom, having discovered the plan in the appendix to William Muir’s 1880 facsimile of The Marriage, arranged the Songs into three parts, I for Innocence, II and III for Experience. Altering only the final sequence (to build to the restored “Divine Image”), he divided each part into three groups of varying numbers of poems as “a series of arches, in both subject and emotion, that marked off the piece into nine clear movements, each inhabiting a certain spiritual climate and progressing ever further in “Shewing the Contrary States of the Human Soul.” While he sees “a sort of plot in the canon,” with its three sections as a progression from childhood to adulthood to maturity, equal musical attention is given the nine song groups as contrasting vocal-symphony movements.

Within that mosaic structure attention is focused on the segueing[e] of one song into the next, their sometimes jolting contrasts, and the orchestrated pauses between movements. Through these musical contrasts and developments Bolcom tries to reflect those of Blake’s poems. All the oppositions between and within texts yield, however, to the symphony’s main contrast between the atonal dissonant complexities of abstract modernism and the more straightforward melodies of various popular genres.3↤ 3 I was assisted with the music by Daniel Goode, a composer of New Music and professor at Rutgers University. Bolcom’s sequence offers him marvelous opportunities for such progress through contrast and reveals Blake’s belated principle of organization as truly inspired.

The opening group provides a strong and upbeat introduction to Innocence. In a manner typical of the piece throughout, we hear a confusing, loud, polytonal, orchestral cacophony out of which a song eventually emerges with its own vision, as here the tenor lifts the piper’s song, a simple tune to fluty pipe and tambourine in bright three-quarter-time swing. The chorus follows with “The Ecchoing Green” in lilting, folksy triple-time with gorgeous choral echoes set off by country fiddle, chimes, and gong. The shock comes when “The Lamb” completely abandons this pastoral primitivism for the begin page 156 | ↑ back to top first of what will be several atonal, operatic soprano pieces through which Bolcom tries to express the more visionary and unearthly Blake of such angelic visitations as “A Dream” and later, Experience’s “An Angel.” We are, however, brought thumpingly back out of the clouds with a kind of “Home on the Range” country-western “Shepherd” baritone solo with fiddle. The children’s choir appropriately initiates “Infant Joy’s” chromatic duet with a maternal mezzo over orchestral chords.

The movement then culminates in a soft-rock, electric jazz “Little Black Boy,” whose drumming beat is intended to underscore Blake’s ultimately nonassimilationist celebration of the boy’s essentially black, sun-inflamed soul. In “Night the Ninth” of The Four Zoas Blake puts the “New Song” of apocalypse into the voice of an African slave in a remarkable musical prophecy of the Afro-American liberation of modern popular music. Bolcom’s mild, folksy rock is performed here, however, by an overwhelmingly white chorus and orchestra. We were listening to it in the middle of black and Caribbean Brooklyn, whose street kids, chanting in repetitive fury from fire escapes and street corners in a Blakean populism of their own, have merged rhythm and rhyme to make it the rap center of the universe. Sensing here a missed opportunity, I wished the composer had ventured further beyond white popular idiom than a little ragtime and modified reggae into more Blakean spiritual-erotical ranges of gospel, rhythm and blues, or soul.

He tends, rather, to put Blake’s wildness into orchestration and things like the fortissimo conclusion of the madrigal sextet’s “Laughing Song” which opens the next movement. This section also includes the melodious lullaby of “Cradle Song” and in waltz time to guitar the first of Morris’s delightful “Nurse’s Songs,” the work’s only strictly musically paired poems. Gratified desire then yields to the angry exuberance of a “Holy Thursday” carol with horns by madrigalists and chorus, a neat choice for the liturgical-pop thundering of Blake’s multitude. “The Chimney Sweeper” explicates such ferocity as that suppressed in its contrastingly pathetic recitation of the sweepers’ plight against the whining euphonium of a sentimental music hall tune while an angelic chorus and clarinet enacts the sweeper’s fantasy liberation. But, the set ends hopefully in F-major piety with “The Divine Image,” serenely hymned by Morris. Part III of Innocence is a mostly classical and modernist movement, far less to my taste, though it introduces the Romantic “Night,” nicely through a meditative “Nocturne” whose instrumental trill, pluck, and rattle bring us Blake’s birds, beetles and crickets. In the shrieking soprano fluttering of “A Dream,” the orchestral clamor and clanging cymbals of “On Another’s Sorrow” and the completely dissonant “Little Boy Lost,” the text is completely lost, only to be recovered in the folk tune of “The Little Boy Found.”

The opening of Experience continues the post-Schoenberg mode for “The Voice of the Ancient Bard” and “Earth’s Answer.” The second movement is more enchanting. Beginning with a “Nurse’s Song,” rendered less bouncy and more plaintive by the addition of wood-winds and harp, Bolcom then places Blake’s “Tyger,” not against “The Lamb,” but the preceding “Fly,” a sad, haunting evocation of human contingency sung to skittish rhythms by the children’s and women’s choruses. “The Tyger” then confronts us with the harrowing forces with which such frail beings must contend in a shouted speech-song mostly by male voices. Bolcom, who said he tried “to make everything clear,” both submits here to the poem’s insistent beating and breaks its familiarity by putting two beats on each first syllable “Ty-y-ger Ty-y-ger

bur-ur-ning bright” against a wild rumbling percussion. The group then concludes with a romantic Mahlerian rendition of “Little Girl Lost” and “Found,” its straight-forward five note melody first relayed acappella between male and female choruses, then, by the time it has taken us to the kingly lion’s hallowed ground, rounded out with rich harmonizing. When the “spirit arm’d in gold” appears, it is encompassed by harmonious orchestration as well, until finally “The Tyger’s” dread is resolved with the Blakean vision of the “sleeping child / Among tygers wild” of its rapturous conclusion.The next three movements continue these contrapuntal styles: “The Little Vagabond” ’s lusty barroom fox trot against the soaring Fs and F sharps above high C of “The Angel” ’s frigid maid, scored to be performed “Silvery, like a princess in an ice-palace” and “A Poison Tree” ’s grim narration against the ominous chords of an atonal piano. The flower group moves from a pretty barbershop begin page 157 | ↑ back to top “Rose Tree,” to the sighing echoes of “Ah! Sunflower” and the complex, chromatic setting of “The Lilly,” making in its own way the piece’s strong argument against finding an illusory simplicity in Blake’s lyrics. The penultimate movement drowns the complaint against childhood repression of “The Garden of Love,” “The Little Girl Lost” and “Infant Sorrow” in its disharmonies, but the Carmina Burana-like “A Little Boy Lost” with boy soprano and chorus drives it home with scary rhythm to a bit of melody picked up, appropriately, from “Holy Thursday.”

Finally, we move toward an apocalyptic finale through the felicitous concluding cluster. The “mind-forg’d manacles” denounced by a rocking “London” are analyzed in “The Human Abstract.” Such spiritual oppression is further exemplified in “The School-Boy” ’s lyric plaint against a stultifying education and “The Chimney Sweeper” ’s denunciation of religion, its tambourines, gong and drum brush capturing the child’s wretched gaiety in what could be either a festive Elizabethan procession or a prison march. These contraries of human self-creation-become-self-destruction sharpen in the slow reggae finale whose terrible vision that “Cruelty has a Human Heart” is sung in cheerful full throated vigor to a too singable, too swingable tune passed with mounting energy from rock singer to full chorus and orchestra. Since you can’t get the tune out of your head for days, the ironies continue to unsettle.

Bolcom claims he learned such juxtaposition from Bob Marley, to whom the song is dedicated, and that, in this dark age, he wanted to end the cycle in celebration, but one is equally reminded of our culture’s hedonistic dance of death on the brink of every kind of economic, political, and ecological catastrophe. Ultimately, this prophetic element is what Bolcom, who spent the 60s studying in California and Paris, says draws him to Blake: “Blake is the most urgent of poets. He came from an epoch of social change as total as ours, and we can learn from him in the times of our deepest crisis. Blake saw where the human race was heading; it could be argued that the Songs of Innocence and Experience may be the clearest explanation of what brought us to this impasse.” The solution he hopes to promote is a greater “acceptance and understanding of our own nature” through “a more careful listening to Blake’s message.”

I’m not sure quite how to assess his achievement. Is this the new American masterpiece that some critics have called it? Is it Blake? Which Blake? I feel too musically inexpert to venture a judgment. The eclecticism and the Neo-Romanticism seem right; one wants the range of heaven and earth, common and sublime that Bolcom attempts. I loved the lyricism, and he has a way with melody that certainly gets you singing those very different “Divine Image” songs. As a whole, however, the piece, written over twenty-five years, may be overwhelmed by its own variety; motifs don’t return often, or, at least, I couldn’t hear the continuity. Thus, unity seems to rest on its most repeated and pervasive style, the post-Schoenberg, post-Berg abstractions and dissonance. I’m not sure what this angst-ridden mode brings to Blake finally; perhaps it articulates some of the alienation, ambiguity, and indeterminacy so prominent in recent readings of Blake. Or is it just what a serious modern composition must sound like?

As for the vernacular, its effect is weakened by Bolcom’s political-aesthetic decision to use mostly classical voices, and I felt that sometimes it was the wrong vernacular. Bolcom’s popular idiom is mostly the milder, nostalgic kind, old folk tunes or turn of the century ballads. His rock made me want something funkier, harder—Pink Floyd, indeed. Though it’s intriguing to imagine Blake as their bond, there’s nothing in Bolcom so rebellious as “We don’t want no education; We don’t want no thought control” (Pink Floyd, The Wall). And where is the Dionysian? For me, it is still Ginsberg who captures Blake’s prophetic seriousness in his passionately committed incantations. I heard Ginsberg get a college auditorium chanting as a fierce refrain, the “Merrily, merrily we welcome in the year” of “Spring” ’s erotic pastoral which, he promised us, sung with sufficient conviction, could resurrect the 60s utopian dream. It has never failed to teach my students more in ten wild minutes about Blake’s contraries than any other introduction. What Ginsberg’s chants or the Labour Party’s bellowing of Parry’s “Jerusalem” capture is that Blake’s poetry must be sung so it can be taken into our yearning bodies and filled with our hearts’ desires.

Even so, it is not just Ginsberg’s but probably two, three, many Blakes that we are wanting and that all these furiously composing musicians like Bolcom will continue to give us. We have been absorbing the lesson of Blake’s “composite art” as providing, in the mutual commentary of picture and text, not a more definitive interpretation, but more interpretive possibilities. This aesthetic, W. J. T. Mitchell has commented, demands creative participation, almost as if we must intuit missing poems Blake could have written to go with the pictures.4↤ 4 W. J. T. Mitchell, Blake’s Composite Art: A Study of the Illuminated Poetry (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1978), 8. Well, there is missing music to go with the engraved poems, and composers like Bolcom remind us that Blake’s Songs bequeath to us an even greater freedom, leaving to the ongoing “wonders Divine of Human Imagination” the interpretive music to which they will be sung.