REVIEWS

William Blake’s 1809 Exhibition. Room 8, Tate Britain. 20 April-4 October 2009.

Martin Myrone, ed. Seen in My Visions: A Descriptive Catalogue of Pictures. London: Tate Publishing, 2009. 128 pp., illus. £12.99, hardcover.

For the bicentennial of Blake’s utterly disastrous 1809 “Exhibition of Paintings in Fresco, Poetical and Historical Inventions,” Tate Britain has recreated the show in its room 8, including ten of the original sixteen pictures. Even though considerable energy and intelligence went into the exhibit and the augmented edition of Blake’s original Descriptive Catalogue published in conjunction with it, the result is no more successful than the original seems to have been in communicating Blake’s ideas or persuading an audience that he had discovered the lost secret of painting. Whereas Blake’s show took place in mundane rooms above the haberdashery shop operated by his brother, the recreated exhibition has the benefit of the exalted cultural domain of the Tate, and the curators may have hoped that this, together with Blake’s greatly improved reputation, might be enough to save the show this time around. But in 1809 all Blake’s pictures were present, including the gigantic painting on canvas of The Ancient Britons (the square footage of which probably equaled the rest of the pictures combined), most of the pictures looked the way Blake wanted them to look, and the relevant cultural and political contexts were at hand. The audience decidedly didn’t get it then. Now we don’t have enough left to figure out what there once was to get.

Only eleven of the original pictures survive. The show includes all ten that are still in Britain, but some of those that are lost, such as The Ancient Britons, may have been essential to understanding Blake’s purposes in mounting the exhibition in the first place. The watercolors in the Tate show are fairly bright and most are bonny, but none of the surviving temperas is in good shape—The Spiritual Form of Nelson, The Spiritual

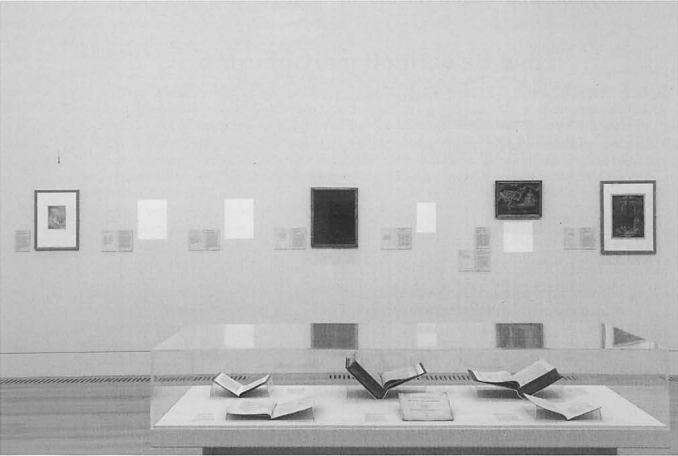

The surviving pictures from the 1809 exhibition are arrayed on the remaining three walls, mostly following the order in Blake’s Descriptive Catalogue, which may have been the sequence in which they were originally displayed. Blank spaces of appropriate dimensions represent lost or absent works, and in some cases related pictures by Blake are nearby: for instance, the Tate’s well-preserved tempera of The Body of Abel (c. 1826) stands in for the somewhat less impressive watercolor of the subject that was actually in the 1809 show (and is now at the Fogg), and the British Museum’s handsome watercolor called As If an Angel Dropped Down from the Clouds takes the place of the lost tempera of A Spirit Vaulting from a Cloud. In one case even the original pictures stands in need of supplementation. The conditions for viewing the fragile and profoundly obscure tempera Satan Calling Up His Legions in room 8 are very good, and a great improvement over those at its home in the Victoria and Albert (where as I recall one must view it flat, under glass, directly beneath a skylight). But even in these circumstances little more than darkness is visible. It might have been edifying if this “experiment Picture” had been accompanied by the “more perfect” (E 547) later version of the same subject at Petworth House, which even today is comparatively successful at making the forms subtly apparent.

One major issue in Blake’s original exhibition was the relationship between vision, light, and darkness; these are of course central to Blake’s work in general, but many of the pictures begin page 98 | ↑ back to top

he exhibited in 1809 prominently thematize light or its absence, as well as explicitly contrasting spiritual and natural vision (at that time a very sore point for Blake, lately stung by the reviews of his Grave illustrations). And though it probably was not quite so impossibly murky in Blake’s day, Satan’s Calling was always expected to challenge the viewer to appreciate Blake’s visions, even when severely deprived of Newtonian light. Darkness was also important in another “experiment Picture” in the 1809 show, The Goats, now lost. Blake explained in his catalogue that it was inspired by an episode in Wilson’s A Missionary Voyage to the Southern Pacific Ocean (1799) in which native women dressed in leaves were stripped naked by hungry shipboard goats. The representation “varied from the literal fact, for the sake of picturesque scenery,” Blake wrote, and though it was “laboured to a superabundant blackness,” he called it to the special attention of the “Artist and Connoisseur” (E 546). The Tate’s gallery label suggests that “Blake may have intended the picture as a joke at the expense of the straight-laced [sic] missionaries,” but while it probably was a joke it probably wasn’t aimed at the missionaries, if only because Blake never mentioned them or their laces.1↤ 1. In a similar misconstruction, the gallery label for the lost picture The Bramins suggests that Blake’s acknowledgement that the “Costume is incorrect” (E 548) refers to the clothing worn by Wilkins, the Englishman who consulted Brahmins in translating the Gita. It is much more likely that Blake erred in representing the garb of the Brahmins. My guess it that not all the goats of the title are four legged, and that Blake mischievously imagined lecherous artists and connoisseurs jostling each other to peer into the superabundant blackness to glimpse the naked dark-skinned women.2↤ 2. For a discussion of a comparable racially charged work by Stothard, see “‘Art Delivered’: Stothard’s The Sable Venus and Blake’s Visions of the Daughters of Albion,” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 31.4 (2008): 529-50, in which I suggest that Visions began as an outraged revisionary reconstruction of Stothard’s picture and the poem it illustrates.But recognizing this gag, if that’s what it was, in the middle of the exhibition hardly helps us to understand Blake’s purposes in general. Certainly The Ancient Britons and Sir Jeffery Chaucer were not jokes, even if the latter had satiric dimensions, and neither were Pitt and Nelson, though they may have been deeply ironic as heroic portraits. The curators (perhaps inadvertently) provide a potentially helpful clue to understanding Blake’s Nelson (1807), in which the pillow behind the martyr’s head generates the impression of a saintly—or Christ-like—aura. The painting itself is in the collection of the National Maritime begin page 99 | ↑ back to top Museum and not in the Tate show: it would have been good if it or another such image of Nelson had been available to contextualize Blake’s apotheosis of the national hero, which borrows more from Hindu than Christian art.

Fortunately, Blake’s Chaucer picture is supplemented not only by the painting that Blake treats in the Descriptive Catalogue as its direct rival, Stothard’s Pilgrimage to Canterbury, but also the large-scale engraving Blake first published in 1810 as well as the long-delayed engraving by Schiavonetti and Heath after Stothard. All three are clustered in one corner of the context wall, a few steps from Blake’s tempera, and for me the close proximity of Blake’s picture with these constitutes the most important element of the 2009 exhibition, in part because it suggests a possible motivation for Blake’s whole show. I am still pretty much alone in believing that Blake’s Chaucer tempera—which is usually thought to have preceded Stothard’s 1806-07 picture even though it is dated 1808—was conceived from the start as a riposte to Stothard’s Pilgrimage,3↤ 3. For some of my reasons see “‘Idolatry or Politics’: Blake’s Chaucer, the Gods of Priam, and the Powers of 1809,” in my collection Prophetic Character: Essays on William Blake in Honor of John E. Grant (West Cornwall, CT: Locust Hill Press, 2002) 100-03. but it may be less controversial to assert that the primary impetus for the 1809 show was to showcase Blake’s “fresco” of the pilgrims as the competitor to Stothard’s oil painting and also to promote Blake’s engraving (just as Cromek’s touring exhibitions of Stothard’s picture were calculated to promote lucrative sales of the projected engraving after it). Blake’s exhibition, an extraordinarily uncharacteristic foray into self-promotion, can be seen as having an unsettled mixture of motivations, at once earnest—he really did want to sell more pictures and engravings to the public at large—and a game, as Chaucer would say, an anxious parody of the sordid promotional hoopla used by Cromek and others to drum up public interest. In order to respond to Cromek’s provocations4↤ 4. In a letter (May 1807) Cromek asks Blake why he detests Stothard’s Chaucer painting and invites him to produce “a better” if he doesn’t like it; see G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004) 241-44. it was not enough for Blake to paint and engrave a Chaucer picture of his own, in the same odd format as theirs (though proceeding in the opposite direction)—he also had to mount his own promotional campaign. This scenario might suggest why the promotion was ultimately so incoherent: it seems likely that Blake didn’t have his heart in commercial puffery, and that in

The rivalry between the Chaucer pictures may have spurred Blake’s exhibition, but rather than presenting only one picture, carrying it from town to town with expensive ballyhoo as Cromek had done, Blake instead brought together an assortment of sixteen works, many of them falling into subject categories popular at the time but rare in Blake’s oeuvre. It’s hard to tell how many besides the Chaucer picture were really for sale, since several had been borrowed from Thomas Butts, the “experiment Pictures” were probably not saleable, and The Ancient Britons was commissioned by William Owen Pughe. Some might have been throwaway parodies (especially The Goats), and others (Pitt, Nelson) may have been created for the occasion as Blake’s ironic alternatives to such dead-celebrity art as Devis’s Nelson or West’s Death of Wolfe. The Bramins could have been a response to the popular genre depicting interactions between Britons and colonial subjects.

I am not sure that a fully coherent conception of the exhibition could have been communicated in room 8 by lining up an ideally suggestive array of contextual works or expanding the wall labels to include more of Blake’s descriptions, but the new edition of Blake’s Descriptive Catalogue that accompanies the show does not go as far as it might have to help us either. This handsome quasi-catalogue by Martin Myrone, curator of the show, is for the most part intelligently executed but not very ambitious. Although the introductory chapter efficiently and even-handedly summarizes scholarly opinion about the 1809 exhibition and much more clearly explains its contexts than the 2009 exhibit itself does, there is little attempt to put it all together or go beyond what has been said about the pictures in Butlin’s Paintings and Drawings of William Blake. The presentation of the complete text of Blake’s catalogue is perfunctory, with informative but uneven notes, and the biographical and glossarial “indexes” at the back are mostly unhelpful and often mysterious. There are good images of the surviving pictures (including the Fogg’s Cain Fleeing, which is not in the Tate show); several, especially The Bard and Satan Calling, appear to have been enhanced so that they reveal much more than can now be seen in the actual pictures.