“a bite”: The First Published Reference to Blake’s Ghost of a Flea?

Angus Whitehead (whitehead65_99@yahoo.co.uk) is assistant professor of English literature at the National Institute of Education, Singapore.

The Literary Gazette was an innovative and widely read weekly literary review initiated by the publisher Henry Colburn in 1817 and edited by the Scottish journalist and antiquary William Jerdan.The firm of Henry Colburn published an impressive and eclectic range of books, including novels, poetry, travel literature, accounts of contemporary warfare, and antiquarian writings and drawings. Colburn published major works such as Samuel Pepys’s diary and (with Richard Bentley) an edition of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, as well as works by “silver fork” novelists Lady Caroline Lamb and Lady Charlotte Bury, both of whom Blake met (see Peter Garside, “Colburn, Henry [1784/5–1855],” ODNB; G. E. Bentley, Jr., Blake Records, 2nd ed. [New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004] [hereafter BR(2)] 333-34). Other notable works published by Colburn include Chateaubriand’s Recollections of Italy, England and America, the poetry of Thomas Campbell, the plays of Joanna Baillie, and the writings of James Hogg. Blake’s acquaintance Marguerite, Countess of Blessington, as well as the poetess and novelist “L. E. L.” (Letitia Elizabeth Landon), appeared first in the pages of the Literary Gazette. The newspaper operated from 5 Catherine Street, just off the Strand, not far from William Blake’s studio-apartment at 3 Fountain Court. On 18 August 1827, just six days after Blake’s death, the Gazette published the first obituary of the poet-artist. While praising Blake’s work highly, it condemns the poet-artist’s neglect by his contemporaries: Blake [has] been allowed to exist in a penury which most artists,—beings necessarily of a sensitive temperament,—would deem intolerable. Pent, with his affectionate wife, in a close back-room in one of the Strand courts, his bed in one corner, his meagre dinner in another, a ricketty table holding his copper-plates in progress, his colours, books …, his large drawings, sketches and MSS.;—his ancles frightfully swelled, his chest disordered, old age striding on, his wants increased, but not his miserable means and appliances: even yet was his eye undimmed, the fire of his imagination unquenched, and the preternatural, never-resting activity of his mind unflagging.Literary Gazette no. 552 (18 Aug. 1827): 541. As Bentley notes, it is likely that the obituary was written by the Gazette’s chief contributor, the art critic William Paulet Carey, a Blake enthusiast and former printmaker.BR(2) 467fn; Nicholas Grindle, “Carey, William Paulet (1759–1839),” ODNB. In a number of pamphlets and articles published between 1808 and 1819, Carey had consistently lauded Blake’s work as an artist, especially his designs for The Grave.See BR(2) 275 (1808), 302 (1810), 330 (1817), and 369 (1819). The pamphlet of Dec. 1817 indicates that Carey had not met Blake by that time (see BR[2] 332). In Dec. 1820 a “William Blake,” together with John Varley and other artists, signed a testimonial as to Carey’s experience and competence to become keeper of “a select and valuable Collection of Paintings, Engravings and other works of Art” (BR[2] 374). The detailed obituary suggests that Carey (or whoever the author was) had actually visited Blake at Fountain Court.

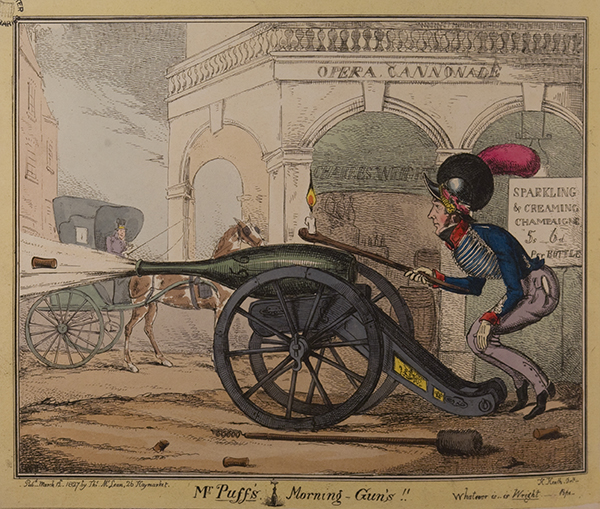

The earliest published reference recorded in Blake Records to Blake’s encounter with the ghost of a flea is the obituary of September 1827 in the Literary Chronicle;Literary Chronicle (1 Sept. 1827): 557-58. See BR(2) 468-70. three months before the poet-artist’s death, however, the Literary Gazette had featured a fleeting reference to the flea. On Saturday, 12 May 1827, below a short review of William Raddon’s recent engraving of Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare, appeared a markedly less sympathetic review titled “Mr. Puff’s Morning-Guns!! K. [sic] [Henry] Heath delt. Published by T. McLean.”Literary Gazette no. 538 (12 May 1827): 300. The title of the print refers to Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The Critic, act 2, scene 2. Mr. Puff at Tilbury Fort exclaims, “What the plague! Three morning guns! There never is but one! Ay, this is always the way at the theatre. Give these fellows a good thing, and they never know when to have done with it” (Richard Brinsley Sheridan, The School for Scandal and Other Plays, ed. Michael Cordner [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998] 320). For a further reference to the subject of the print and Mr. Puff, see “Twelfth Night at Almack’s,” London Magazine (1 Feb. 1827): 205.

The author of the review, almost certainly Carey, writing in the spring of 1827 and still within Blake’s lifetime, is clearly confident that his readers will recognize a reference to Blake as “the illustrator of ‘The Grave,’” thereby suggesting that Blake remained a familiar name two decades on. The brief allusion to the caricature of a flea appears to assume that some of the readers were also familiar with Blake’s encounter with the “spiritual apparition of a Flea”John Varley’s description in his Zodiacal Physiognomy (1828); see G. E. Bentley, Jr., The Stranger from Paradise: A Biography of William Blake (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001) 377-78. sometime between 1819 and 1825, the period in which Blake and John Varley’s midnight séances took place at Blake’s residences at 17 South Molton Street and later Fountain Court.See BR(2) 346-69. However, the reviewer wrongly identifies Blake’s partner as “C. Varley,” the inventor and painter Cornelius, rather than his elder brother, the astrologer and landscape artist John. Martin Butlin has proposed that copies of the visionary heads may have been made using Cornelius Varley’s patented graphic telescope,See Martin Butlin, “Blake, the Varleys, and the Patent Graphic Telescope,” William Blake: Essays in Honour of Sir Geoffrey Keynes, ed. Morton D. Paley and Michael Phillips (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973) 294-304. but Cornelius is not known to have had any other involvement with the project. Either the Gazette’s reviewer was poorly informed, or (less likely) it is a typo (C. for J.). In any case, the fleeting reference suggests that Blake’s encounter with the ghost of a flea was already a story familiar among literary and artistic circles in the metropolis.

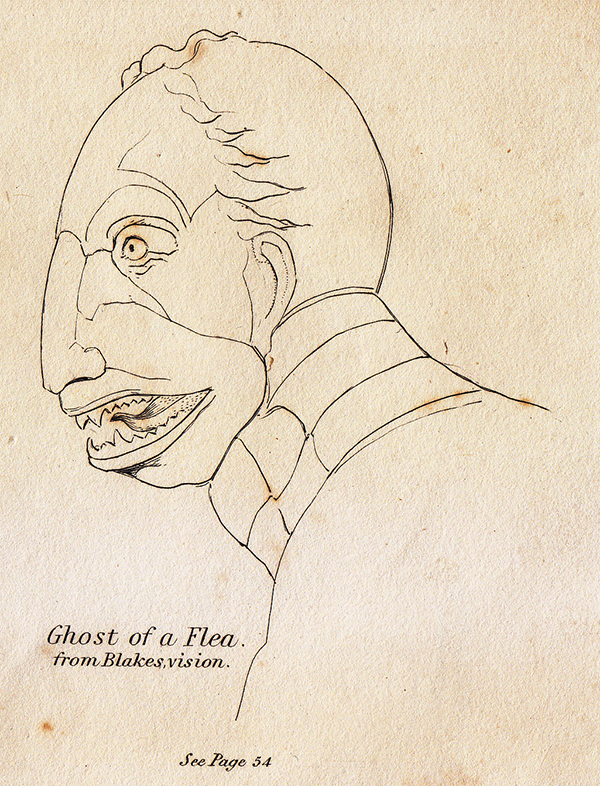

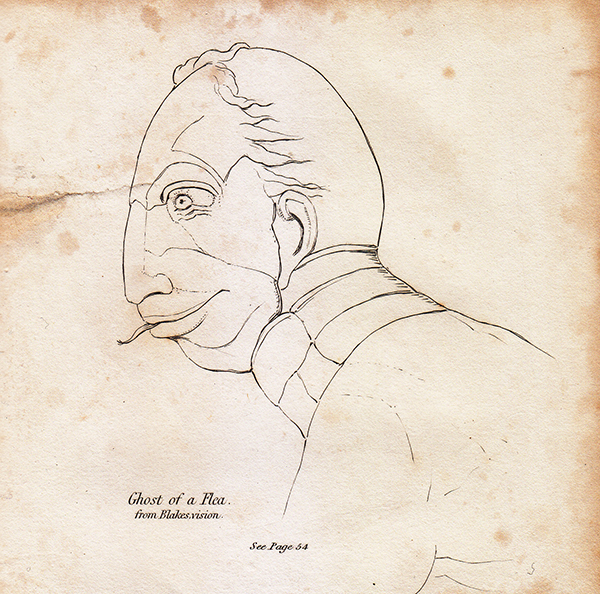

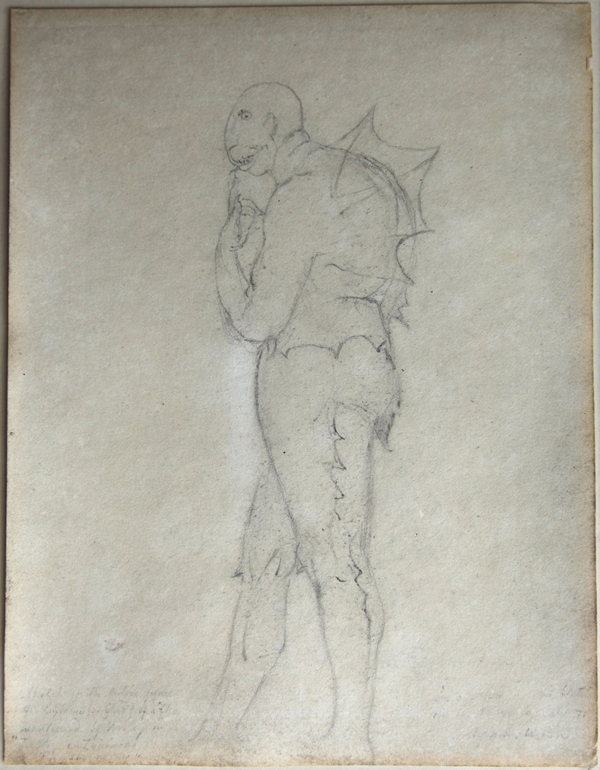

The reviewer also mentions that Varley and Blake “caricatured a flea.” The idea that Blake’s drawing, as much human in shape as flea, is somehow satirical in nature is a novel one, differing from John Varley’s and Allan Cunningham’s later accounts. The suggestion is of interest, as eighteen months later Blake’s representation of the ghost of a flea would enter print culture through John Linnell’s engravings for Varley’s Zodiacal Physiognomy (illus. 2).

In its attack on Heath’s print and its subject, the review goes on to mention three other London “quacks,” or insistent self-publicists, of the period: “Waterton the traveller” refers to naturalist Charles Waterton, who wrote, “I have attacked and slain a modern Python, and rode on the back of a Cayman [South American crocodile] close to the water’s edge; a very different situation from that of a Hyde-park dandy on his Sunday prancer before the ladies.”Charles Waterton, Wanderings in South America, the North-West of the United States, and the Antilles, in the Years 1812, 1816, 1820, and 1824 (London: J. Mawman, 1825) 242. “Dr. Eady” was a notorious and apparently mentally unstable medical swindler operating in London during the mid-1820s.See “Annals of Quackery. Caution to the Public. Eady’s Escape from St. Luke’s!” Medical Adviser, and Guide to Health and Long Life (17 July 1824): 77-79. In his allusion to “the Blacking Manufacturers,” the reviewer is referring to Robert Warren’s blacking manufactory at 30 Strand, several blocks west of the premises of the Gazette. The author and journalist William Frederick Deacon, Warren’s friend, produced a book of parodies of contemporary poets dedicated to the king, with each parody praising Warren’s blacking.See Warreniana (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1824). T. A. B. Corley notes that “Warren was one of the first to market a nationally advertised household product in Britain. His press publicity featured verses; one poet, Alexander Kemp, boasted of having written two hundred of these offerings. A popular theme, of a cat spitting at its reflection in a well-blacked Hessian boot, was illustrated by George Cruikshank.”T. A. B. Corley, “Warren, Robert (1784/5–1849),” ODNB. Warren, then, pioneered advertising techniques, including verse and print culture, to promote and sell his product—techniques soon utilized by Wright in the advertising of his champagne.

As the reviewer recognizes, some of these “quacks,” notably Waterton, were not averse to celebrating their eccentricities for notoriety, publicity, and self-gain. After discussing these four hoaxers or self-promoters, he makes the brief allusion to Blake: “C. Varley and Blake … caricatured a flea … also a bite.” As the italics suggest, bite was contemporary slang or cant. The OED defines it in this context as “an imposition, a deception; what is now called a ‘sell’; passing from the notion of playful imposition or hoax, to that of swindle or fraud.”The OED notes that this term was used as early as 1711 by Richard Steele in Spectator no. 156: “It was a common Bite with him, to lay Suspicions that he was favoured by a Lady's Enemy.” In describing Blake’s drawing of the ghost of a flea as “a bite,” the reviewer appears to be making a series of puns, firstly on “bite” simultaneously referring to hoaxes and flea bites and secondly on “noxious insects” simultaneously referring to four celebrated quacks and the subject of Blake’s “caricature.” In addition, he situates Blake and Varley and the ghost of a flea as a notorious contemporary phenomenon in the same category as the productions of the cayman-riding Waterton, the medical quack Eady, Warren the blacking manufacturer, and Wright the purveyor of sham champagne. Cunningham and later Blake biographers have represented Blake’s flea encounter as evidence of the poet-artist’s eccentricity, madness, or visionary abilities.See, for example, Allan Cunningham, The Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (London: John Murray, 1830) 2: 167-71; Bentley, The Stranger from Paradise 368-82. However, James King has suggested that Blake may have been humoring or playing a joke on his friend: Blake’s resulting drawing owes more to the engraving of a flea under a microscope in Robert Hooke’s Micrographia, where the proboscis of the insect is described as “slip[ping] in and out’, than to a visionary experience. Although Blake had a powerful eidetic imagination, the appearances of Achilles, Corinna, Laïs, Herod, Edward I and William Wallace smack more of tomfoolery on Blake’s part than a serious interest in phantoms of the night.James King, William Blake: His Life (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1991) 214-15. See also Robin Hamlyn and Michael Phillips, William Blake (London: Tate, 2000) 190.

The Literary Gazette review suggests that in the spring of 1827 Blake’s vision and drawings of the ghost of a flea were not necessarily regarded as evidence of either his madness or visionary imagination, at least for the writer and some of his readers. Instead, like King, some contemporaries may have interpreted the encounter as a knowing deception. For the reviewer, however, the ghost of a flea is not a case of Blake’s humoring Varley, but rather a hoax manufactured by the poet-artist and his friend. Accurately or not, he appears to imply that they consciously concocted and encouraged the story for the sake of notoriety and publicity. For him, if the ghost of a flea is “a bite,” the joke is not on Varley, but on contemporary (and perhaps future) “gulls” in London and “fools … spread over the whole land.” And yet Blake and Varley’s imagined flea is regarded by the reviewer as “more respectable and much worthier” than the “puffing species” of Wright, Warren, Waterton, and Eady.